When the Bambino Came to the Port City©

Nearly one hundred years ago, on Wednesday March 25, 1914, the greatest baseball players ever to grace a ball field in Wilmington squared off in Sunset Park. The Philadelphia Athletics, the game’s most successful and prestigious professional baseball team, traveled to Wilmington to play the Baltimore Orioles. Managed by Connie Mack, the A’s were the defending champions who had won three of the previous four World Series. The local papers called it “the biggest game of baseball Wilmington has ever witnessed.” In all, seven future Hall of Famers were on the field that day: Frank “Home Run” Baker, Chief Bender, Eddie Collins, Connie Mack, Herb Pennock, Eddie Plank and Babe Ruth.

Aside from the normal antagonism that might be expected in a game between the World Champions and the underdog minor league challengers, the air was rife with tension caused by numerous extraneous factors. The drumbeats of an impending war in Europe reverberated through the ranks of young ballplayers preparing for the baseball season, knowing that soon their country might need them to prepare for war. The emergence of the rival Federal League distressed existing teams that watched as players were paid exorbitant sums to defect to the new league. Uncertainty and a fatalistic ‘who’s the next to leave’ permeated the clubhouses. Daily reports of players embroiled in litigation added to the anxiety level. The game between the Athletics and the Orioles became a pressure release valve.

The Athletics had just completed training in Jacksonville, Florida and were traveling north, playing along the way home to stay sharp. They were unbeaten over the previous two weeks and were primed to defend their title. By contract, the Athletics, also known as the White Elephants on account of their unique emblem, committed to playing its regulars, including the famous “$100,000 Infield.” Featuring future Hall of Famers, second baseman Eddie Collins and third baseman Frank Baker, along with shortstop Jack Barry and first baseman Stuffy McInnis, Connie Mack’s infield is regarded by baseball historian Bill James as the greatest infield of all time.

The cleanup hitter for the powerful A’s was the big leagues’ reigning home run king, Frank “Home Run” Baker. He had earned the nickname for his heroics in the 1911 World Series when he blasted a go-ahead homer in game two and a dramatic ninth inning game-tying home run off Christy Matthewson in game three. In an era where the home run was a rarity, Frank Baker led the American League four straight years starting in 1911 with eleven dingers, 1912 with ten, 1913 with twelve and 1914 with nine homers. Little did Baker know that on that memorable day in Wilmington, he would be batting against the man who would obliterate his home run records, none other than the Bambino, George Herman “Babe” Ruth.

Another notable on the A’s roster was pitcher Colby Jack Coombs, Connie Mack’s half brother. In 1910, Coombs had one of the greatest seasons ever, winning thirty-one games and setting the record for consecutive scoreless innings (53). When his playing days were over, he went on to a distinguished career as the baseball coach for Duke University for twenty-three years.

In contrast to newspaper hype of the luminaries on the A’s, stories about the Orioles focused on second baseman, Neal Ball, whose claim to fame was that he was the first major leaguer to record an unassisted triple play. The unbeatable feat occurred while he was playing for the Cleveland Indians. With two men on and a full count, the opposing manger signaled a hit and run. The runners broke on the pitch. Ball caught a screaming liner, stepped on second base for the second out and then tagged the runner from first. It happened so fast that Cy Young who was pitching for the Indians, asked Ball where he was going as he headed for the dugout. Although the Orioles played in the International League, they were more than capable. Most of the Orioles had played in the big show. They had already swept the Phillies in three spring training contests. If the challenge of playing against the best was not enough, the Orioles were motivated to demonstrate that they had the ability to play on a major league level, in whatever league would pay them.

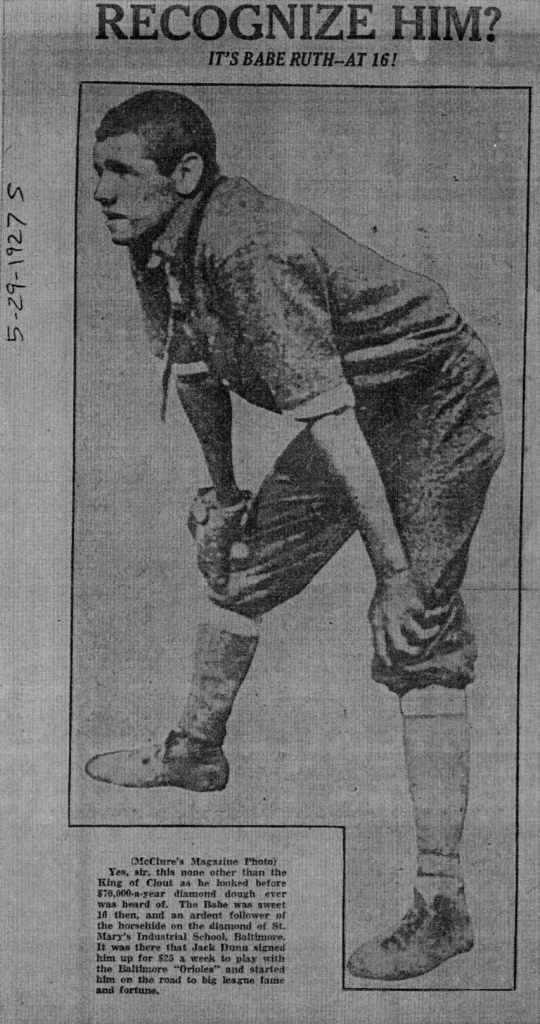

On the morning of the game, the Orioles took the Palmetto Limited to Wilmington from their training base in Fayetteville. Ruth was an unknown rookie who had signed his first professional contract one month earlier, just days after his nineteenth birthday. It would be his first start as a pitcher on a professional baseball team. According to local lore, the game was played in Godwin Stadium, Babe Ruth hit a home run and struck out Home Run Baker three times. Although the Babe pitched a complete game victory and bested Baker in a surprising way, none of these conventional beliefs are accurate.

A year earlier, the first game involving major league teams had been played in the Port City and Wilmington was smitten by baseball fever. In an amazing display of civic pride, efficiency and commercial opportunism, the Port City staged one of the “biggest coups” ever. In those days, baseball teams did not have set spring training camps. Each year they jumped from one municipality to the next, depending on the incentives offered. During the previous fall and winter, a group of Wilmington business leaders cajoled, courted and convinced the Philadelphia Phillies to leave their spring training facilities in Southern Pines, N.C. and hold spring training in Wilmington. They established a private corporation to construct a state of the art training facility and stadium. Using funds from private subscribers, they built a baseball field at Central Boulevard and Adams Street that was a short trolley ride from downtown. The developers sponsored a contest to name the area. Montrose Bain, the Circulation Editor of the Wilmington Morning Star, won with the entry Sunset Park.

In the months before spring training, the progress of the construction of the park was closely followed in the news. The Philadelphia team sent an experienced ‘landscape gardener’ to oversee the installation of the turf. When the Philadelphia reporters arrived in Wilmington, they gushed in their praise for the new complex. “The residents have been pointing to it [Sunset Park] . . . with pride till their index fingers are wearing off. A spacious grandstand backs the field. Beneath are the players’ quarters. Hot and cold shower baths, Turkish bath apparatus and lockers are only some of the advantages.” Consequently, when it was announced that the World Champion Athletics would play at the new stadium at Sunset Park, there was great excitement.

Life was much different a century ago. For instance, the price of a “healthy invigorating, refreshing Pepsi Cola At Soda Fountains or Carbonated in Bottles” cost only five cents. So, too, were ten ‘mild and pure’ Reyno cigarettes. Tickets to the game were sold at local eateries, pharmacies and at five area cigar shops until two hours before game time. General admission was fifty cents and it cost an additional quarter for grandstand seats. The Morning Star reported that an immense crowd of several thousand “ . . . taxed the capacity of the commodious Sunset Park grandstand and overflowed the bleachers.”

Much of the language associated with the game was different from today’s usage. Reports of the game include numerous quaint and unique phrases that would be unfamiliar to the modern day fan. For example, fans were called cranks, owners were magnates, teams were aggregations, players were ball tenders or ball tossers, walking was called franking, the outfield was known as the garden and a swatter who drove in a run was the candy kid. The pitcher was a box artist who twirled the pill.

The Athletics started pitcher “Boardwalk” Brown, a lean, righthander whose colorful nickname came from his days playing on the sandlots of Atlantic City. He was in his third year with the Athletics having played on the American League pennant winners in 1911 and 1913. Before the crowd had settled into their seats, Brown was in trouble. Baltimore’s leadoff batter reached first on an errant throw by the shortstop and scampered to second on the wild throw. With two outs, centerfielder Birdie Cree, a former Yankee, broke the ice by singling in the first run of the contest. The Birds threatened to blow the game open by loading the bases; however, the Athletics stiffened and the Birds left the bases loaded.

The crowd gave Frank “Home Run” Baker a huge ovation and he responded by putting on a hitting show. Unfortunately for the White Elephants, his base running left a lot to be desired. In the third inning, Baker was the candy kid, driving in Eddie Collins with a liner t o center to tie the score. Baker was thrown out trying to stretch his hit into a double.

o center to tie the score. Baker was thrown out trying to stretch his hit into a double.

With the game tied after five innings, Connie Mack replaced Boardwalk with future Hall of Famer, Herb Pennock. He did not fare well. Wilmington’s daily newspaper reported the action.“Baltimore shot Pennock to pieces in the sixth inning . . . putting four men across and winning the game.”

Although Baker stroked four hits of the thirteen hits that the Athletics collected along with four walks, the teenage Ruth keep them at bay with guts and guile. In the words of A’s star Eddie Collins, quoted by Ruth biographers, Paul Adomites and Saul Wisnia, “’Ruth is a sure comer. He has the speed and a sharp curve, and believe me, he is steady in the pinches,’ an obvious reference to the 13-hit, two-run performance.”

Trailing 6-2 in the bottom of the ninth, the Athletics rallied against the rookie left hander. Baker crushed another hit that was destined to be a double. However, rounding first, he “stumped his toe” and returned to first. “A moment later Ruth caught him napping off his station with a neat peg,” according to the Morning Star. That ended any chance of a comeback by the Athletics, and, more than anything else portended the future emergence of Babe Ruth as the most dominant player of his, or any, era.

The Athletics went on to win ninety-nine games that season, but, were denied another championship when they were swept in the World Series by the Boston Braves. Babe Ruth started the season in the minor leagues with Baltimore, and was sold to the Red Sox where he made his major league pitching debut at Fenway Park on July 11, 1914. In the years that followed, more Wilmingtonians than could possibly have attended the game at Sunset Park would boast about the time that the Bambino came to the Port City.

*Frank Amoroso is the author of the historical novel Behind Every Great Fortune™, released Feb. 21, 2014. The protagonist of this book is Otto Kahn, the Monopoly® man. Set in the turbulent second decade of the 20th century, it chronicles the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, the murder of Rasputin and the bloody devastation of WWI. Email: Frank@BehindEveryGreatFortune.com.